Why do cars by Industrial Designers and Architects suck so badly?

Friday, April 23, 2010 at 9:55PM

Friday, April 23, 2010 at 9:55PM I have recently been reflecting on how many designers and architects over the years have tried their hand at automotive design. and failed. Miserably. Many professional Industrial Designers deride automotive designers as "Stylists" and apparently the auto guys took it personally. Back in the old days, "Styling" was what they did. But now "styling" is a dirty word, and no self-respecting car designer would refer to himself (or herself) as a stylist. A "real" designer is supposed to solve problems, and change the world. The idea of sculpting sheet metal over what is essentially a slowly evolving mechanical package seems uttlerly banal compared to this type of big picture thinking. Right? Wrong. Because from Raymond Loewy and Brooks Stevens all the way through to Philippe Starck and Zaha Hadid, "real" designers have consistently proven themselves not up to the task of creating automotive concepts that stir the soul. And frankly, as an Industrial Designer, I think it is time to give car designers their due and stop thinking we can best them at their own game.

In my field, the idea of doing something because it "looks right" has become such an anathema that we are forced to construct elaborate BS smokescreens around what are essentially irrational right brain decisions about form. But car design is a place where something can "look right" because it "is right." Obviously, the age of focus groups and brand management has diminished the artistic aspects of the auto design profession, but from where I sit, today's car designers have still proven themselves capable of some remarkable flights of brilliance that can take your breath away. But I digress. I thought I would prove my point by assembling a gallery of horrors showing some of the worst "designer" cars of all time.

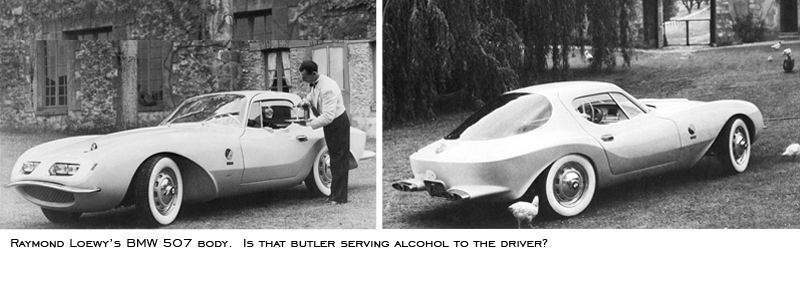

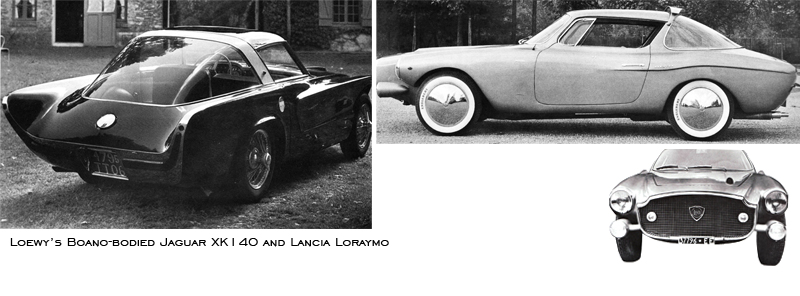

Raymond Loewy was perhaps the most prominent example of a world class Industrial Designer who thought of himself as a born gift to car design, yet he had no real sensitivity to the automotive form and very questionable taste. Every car he owned - and there were many - he had modified to his tastes. Mostly, this was to the detriment of the car's appearance. Starting with his modified Lincoln Continental, all the way through his rebodied BMW 507, Jaguar XK140, Lancia Flaminia, and '59 Cadillac he created one ghastly ego-trip after the next.

He then had the cojones to claim that auto manufacturers like Porsche copied design features from his car concepts. In particular, he claimed that the Lancia Loraymo's spoiler was adopted by BMW for the 3.5CSL, and that the C Pillar from his Boano-bodied Jaguar was appropriated by Porsche for the 911 Targa. Ok, Raymond, if you say so.

He then had the cojones to claim that auto manufacturers like Porsche copied design features from his car concepts. In particular, he claimed that the Lancia Loraymo's spoiler was adopted by BMW for the 3.5CSL, and that the C Pillar from his Boano-bodied Jaguar was appropriated by Porsche for the 911 Targa. Ok, Raymond, if you say so.

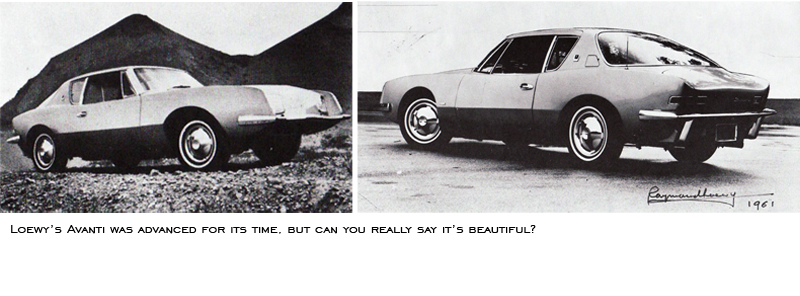

In addition to these one-offs, Loewy did a few production cars for Studebaker which were actually handsome, but these all involved the teamwork of actual car designers (led by "Stylist" Bob Bourke) rather than Loewy's singular hand. The most famous of Loewy's car designs is the Avanti, which was produced originally by Studebaker. I know the car has a loyal following and I also know it was the first car with backlit gauges (an idea adapted from aircraft) but I just think the Avanti is mediocre at best. It has a ghastly C pillar that does not flow well, and the front end design is rather ungainly as well. There isn't a single angle from which it looks right. None for me, thanks.

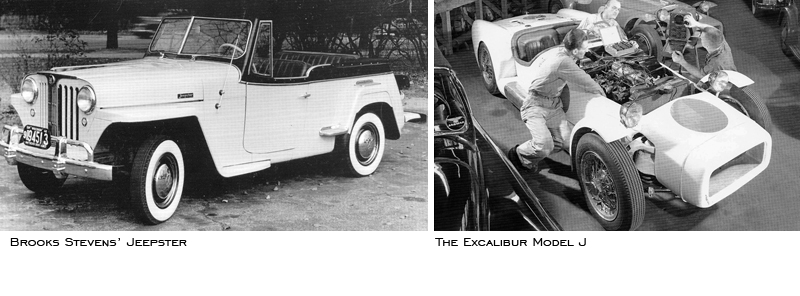

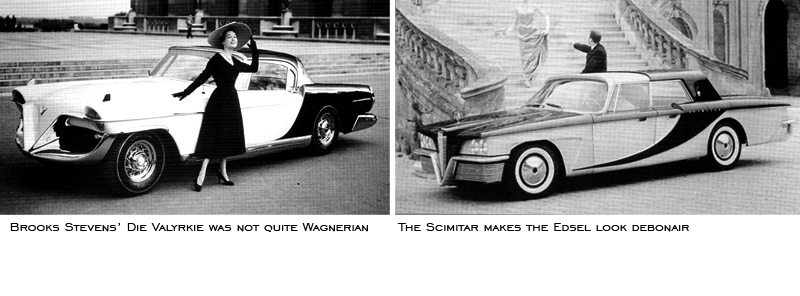

If Loewy's design excercises are poor, then those of Brooks Stevens are positively horrific. The Milwaukee based designer was a true car nut, but like Loewy his belief in his own abilities as a car designer far outstripped his talent for it. One of his earliest creations was a custom body for his Cord L-29. Now restored, I have seen the car in person at a Stevens exhibit held a few years back. While pleasing, it hardly holds a candle to bodies by Cord's in-house "stylist" Al Leamy. Like Loewy, Stevens also possessed a Lincoln Continental which was customized in 1955 with whitewall tires, chrome wire wheels (!), exposed spare tire, and two tone paint. As for production cars, Brooks Stevens was behind the "Jeepster" and Jeep Station wagon (which might be the first postwar "Sport Utility Vehicle"). While quaint in hindsight, these cars have little aesthetic merit. Other ill-conceived designs followed such as "The Scimitar" and "Die Valkyrie" which led to the ironic, yet fitting situation of Stevens succeeding Raymond Loewy as Studebaker's "design guru" right up until they finally went under.

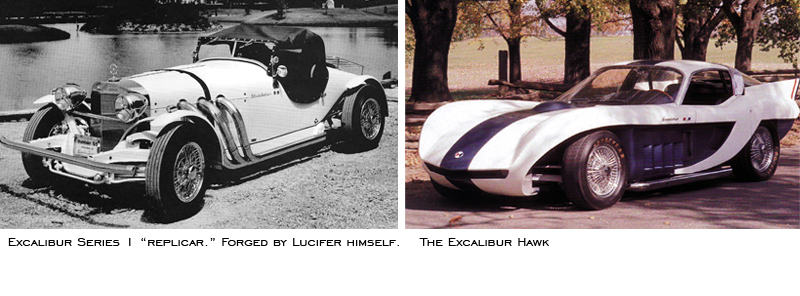

I could go on about these cars, but what I really want to talk about is the dreaded Excalibur. The first Excalibur was the model J, a racing car built in 1952 by Stevens on a Henry J Kaiser platform. In appearance the car resembles a Lotus 7 after eating 2 dozen donuts daily for a year. To his credit, Stevens wanted to create an American sports car that could hold its own against Jaguars and other imported delicacies. In 1962, he created the "Excalibur Hawk" which was decidedly modern, but clumsily executed with then-outmoded tailfins (on a race car?) and chrome wire wheels (on a race car?). It is clear that Stevens was more interested in designing fast poser cars than developing fast racing cars. Too bad that "Stylist" in Detroit by the name of Bill Mitchell created the Corvette Stingray at about the same time, which puts the Excalibur Hawk to shame. Having given up on developing a racing car, Stevens had the idea in 1964 to create a old-timey body on a modern Studebaker chassis. And so the "replicar" was born. The first production Excalibur was the Series 1, modelled after the Mercedes SSK from the prewar years. Though thoroughly Studebaker underneath, the car wore false side exhaust pipes, cycle fenders, and even a leather hood strap. Stevens' entrepreneurial sons produced the cars, and more imitator companies were formed, growing a fad for "contemporary classic" cars as Stevens called them. Or "replicars" as most people call them. Perhaps it is fitting that Stevens is best remembered for his longest-lasting creation: The Oscar Meyer Wienermobile. It has the distinction of being the only car he designed that was intentionally silly looking.

I could go on about these cars, but what I really want to talk about is the dreaded Excalibur. The first Excalibur was the model J, a racing car built in 1952 by Stevens on a Henry J Kaiser platform. In appearance the car resembles a Lotus 7 after eating 2 dozen donuts daily for a year. To his credit, Stevens wanted to create an American sports car that could hold its own against Jaguars and other imported delicacies. In 1962, he created the "Excalibur Hawk" which was decidedly modern, but clumsily executed with then-outmoded tailfins (on a race car?) and chrome wire wheels (on a race car?). It is clear that Stevens was more interested in designing fast poser cars than developing fast racing cars. Too bad that "Stylist" in Detroit by the name of Bill Mitchell created the Corvette Stingray at about the same time, which puts the Excalibur Hawk to shame. Having given up on developing a racing car, Stevens had the idea in 1964 to create a old-timey body on a modern Studebaker chassis. And so the "replicar" was born. The first production Excalibur was the Series 1, modelled after the Mercedes SSK from the prewar years. Though thoroughly Studebaker underneath, the car wore false side exhaust pipes, cycle fenders, and even a leather hood strap. Stevens' entrepreneurial sons produced the cars, and more imitator companies were formed, growing a fad for "contemporary classic" cars as Stevens called them. Or "replicars" as most people call them. Perhaps it is fitting that Stevens is best remembered for his longest-lasting creation: The Oscar Meyer Wienermobile. It has the distinction of being the only car he designed that was intentionally silly looking.

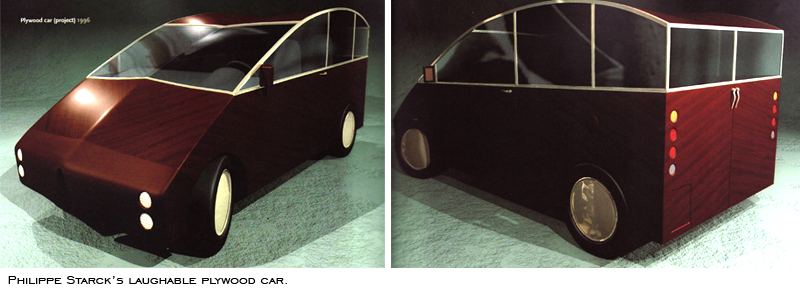

Let's skip forward in time now, and look at the work of French Superstar designer Philippe Starck. Arguably the most famous living designer today, the Frenchman has a number of vehicle concepts to his credit. He is known as a lover of motorcycles and is usually seen wearing a rumpled Dainese motorcycle jacket. Among his produced designs is a rather stylish bike he did for Aprilia in the 90s. But from what I have heard from a French friend test-rode one "C'est du crap." All this is neither here nor there, because when Starck puts his mind to the automobile, he hits a rather sour note. Given his proclivity towards flamboyant form and useless poetic objects, one might expect him to love the Gallic confections of the 1930s like Figoni-bodied Delahayes. But in fact, he has been quoted mainly extolling the virtues of the Mini-Moke and of military vehicles. In both cases, he waxes poetique about the utilitarian "form follows function" aspect of these cars, all the while savoring -with a nod and a wink- the obvious contradictions that this brings about when compared with his own work (imagine a supermodel being asked to wash dishes and you get the basic idea of how his work functions in the real world). Starck's 1996 "Plywood Car" concept shows such a staggering lack of understanding of vehicle dynamics, safety, production techniques, etc that I don't even feel the need to explain why it sucks. Just look at the picture. It's rolling cabinetry. At least when you inevitably die in a crash, it can double as your coffin.

Let's skip forward in time now, and look at the work of French Superstar designer Philippe Starck. Arguably the most famous living designer today, the Frenchman has a number of vehicle concepts to his credit. He is known as a lover of motorcycles and is usually seen wearing a rumpled Dainese motorcycle jacket. Among his produced designs is a rather stylish bike he did for Aprilia in the 90s. But from what I have heard from a French friend test-rode one "C'est du crap." All this is neither here nor there, because when Starck puts his mind to the automobile, he hits a rather sour note. Given his proclivity towards flamboyant form and useless poetic objects, one might expect him to love the Gallic confections of the 1930s like Figoni-bodied Delahayes. But in fact, he has been quoted mainly extolling the virtues of the Mini-Moke and of military vehicles. In both cases, he waxes poetique about the utilitarian "form follows function" aspect of these cars, all the while savoring -with a nod and a wink- the obvious contradictions that this brings about when compared with his own work (imagine a supermodel being asked to wash dishes and you get the basic idea of how his work functions in the real world). Starck's 1996 "Plywood Car" concept shows such a staggering lack of understanding of vehicle dynamics, safety, production techniques, etc that I don't even feel the need to explain why it sucks. Just look at the picture. It's rolling cabinetry. At least when you inevitably die in a crash, it can double as your coffin.

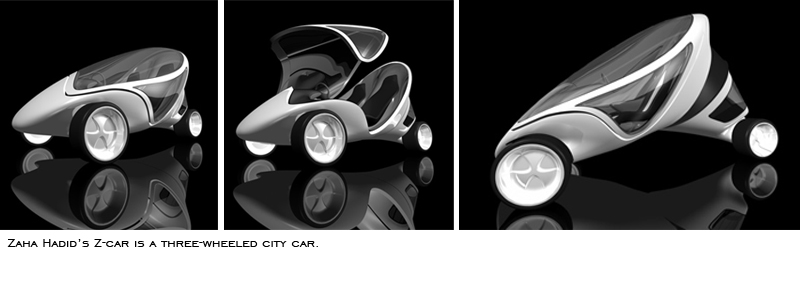

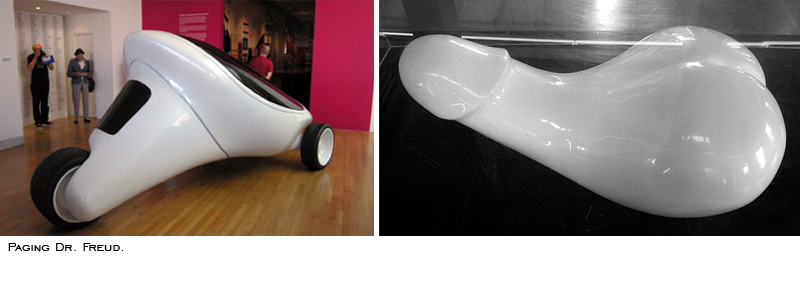

Next and last victim here is noted "Starchitect" Zaha Hadid. While I generally find her architecture exuberant and energetic in the ways that good car designs are, I really wish she'd stick to designing car factories and furniture, with the occasional designer fetish object thrown in. But like her predecessor in architectural megalomania, Le Corbusier, she has tried to re-imagine the ideal "city car." Corb's 1925 concept was interesting, made some mechanical sense, and borrowed much from his friend Gabriel Voisin's aerodynamic visions. Ultimately, though, the great architect was reduced to carping in his letters to FIAT's honcho Agnelli for turning down his offer to license his design to them. Hadid's "Z-car" (apparently Nissan isn't suing her, which is a real shame) doesn't quite live up to even Corb's effort. The glossy white three-wheeler looks a lot like the fiberglass phallus sculpture that is used to bludgeon a woman to death by the protagonist in Kubrick's "A Clockwork Orange." It has a distinct "aero" look which recalls student work from Art Center in the 1980s, or perhaps a sketch that Luigi Colani threw away. There is little to nothing truly innovative about the car, and as a pure form exercise, it really has little to recommend it when compared with many of the truly interesting city car concepts done by Toyota and GM's China division in the last few years. There is little thought given to ingress/egress (how does the passenger exit the car if the door hinges to the side?) and seemingly no storage space for purchases or luggage, unless the area behind the passenger compartment is for that. But then where would the motor be? In the wheels, I guess?

Ok, so my acerbic rant is over. I am a meanie, I know. But I am trying to make an essential point here: Car "Styling", despite noble notions of the universality of "Design" is really an art form unto itself that requires very particular sensitivities and an emotional approach to form giving. Many car designers are not that adept at restraint when trying to give form to static objects, but the difference here is that most car designers don't go around trying to proclaim that they are capable of designing just about anything and everything. Instead they are specialists, and I think more Industrial Designers and Architects ought to give credit to those specialists rather than deriding them as Stylists. Because when it comes time to put up or shut up, most of us "real" designers couldn't design a car to save our lives.

Ok, so my acerbic rant is over. I am a meanie, I know. But I am trying to make an essential point here: Car "Styling", despite noble notions of the universality of "Design" is really an art form unto itself that requires very particular sensitivities and an emotional approach to form giving. Many car designers are not that adept at restraint when trying to give form to static objects, but the difference here is that most car designers don't go around trying to proclaim that they are capable of designing just about anything and everything. Instead they are specialists, and I think more Industrial Designers and Architects ought to give credit to those specialists rather than deriding them as Stylists. Because when it comes time to put up or shut up, most of us "real" designers couldn't design a car to save our lives.

Brooks Stevens,

Brooks Stevens,  Philippe Starck,

Philippe Starck,  Raymond Loewy,

Raymond Loewy,  Zaha Hadid,

Zaha Hadid,  designers,

designers,  stylists in

stylists in  History,

History,  Musings

Musings